"I am still astonished for a better word that the vast majority (read nearly 100%) of dedicated rifle competitors that do not have coaches, I assume this is due to the fact that most shooters are an individualistic mob, and the word team has a rather loose term when it comes to competing in team events, we tend to pull together a fixed number of highly successful individuals and then call them a team, it doesn't work that way folks.

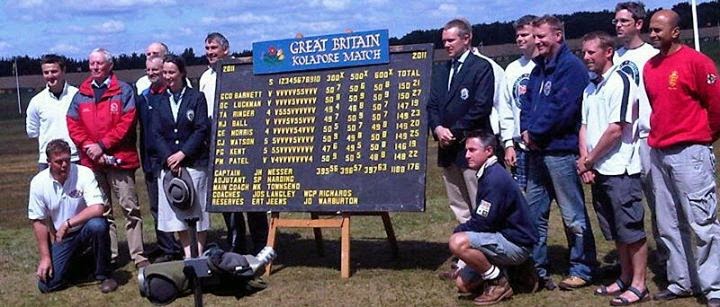

A stand out from the crowd are the British Teams, and any teams that have the majority of members that are military or ex military as are trained and know how and do operate in a team environment, their results reflect this the majority of times, this is an insight one how as shooters we predominantly think from my observations.

So do yourself a favour go find a coach or mentor that can add value to what your are trying to achieve, remember if you want the same outcome you just keep doing what you're doing and it is guaranteed.

This is not about teams, but how we tend to work, how long has it been now 1, 5, 10, 15 years since you have seen an improvement?

Do yourself a favour. here are some start points to move forward.

• Ballistics and equipment ,Bryan Litz great books and articles

• Setting up a rifle (I can hear it now) I know how to do this, guess what you don't, David Tubb has a video that explains how to set up a rifle, invaluable advice.

• Psychology, process, training and practice, Lanny Bassham absolute gold mine of information.

So find someone to help you."

This is probably one of the most insightful pieces of commentary I have read on the state of coaching* in fullbore rifle shooting. For me it captures both the problem and the solution.

Why don't we have coaches now?

I can only really speak for the UK, but there's something of a coaching gap between juniors and the international levels of the sport. Most people start of as shooters in the cadets, where they get taught the basics by cadet officers who are often keen amateur shots themselves, or they come from shooting families and get taught by their parents, uncles or aunts. Once they leave school and start university there's something of a void. Although partially filled by University clubs, very often the standard of coaching is variable at best and occasionally people just get taught to do the wrong thing. Once the education system is a thing of the past, there's not a lot in the way of organised coaching and I'm not even sure how much of an appetite there is for it. As Tony says, many people seem to want to just bang rounds down the range wishfully thinking it will make them better shots.

By way of example, various members of an association of which I was (and continue to be) a full member had voiced complaints that the small number of senior international shooters who were members never passed on any of their skills to other members. I volunteered to run a training skills weekend, which included a review of technique, training, psychology etc... Attendance was miserable, not least by those who had originally made the complaint. I had tried something similar with another association and had much the same result. People would turn out for matches (selection was more or less guaranteed if you could hold any kind of group) but not for any form of training.

I have bad news, and then again I have good news...

The bad news is that I don't really see this changing a great deal, unfortunately. While some of the clubs are making an effort, a lot of others aren't (and indeed in some cases have rules which preclude useful sessions like running SCATT training sessions in their clubhouses.)

The good news is that all is not lost for those who do get the value of having some independent advice. Many (but not all) senior TR shooters are perfectly willing to be approached for advice, but there are so many things you can do for yourself also:

- As Tony suggests, get educated! There's a huge amount of information available for nothing on t'internet from the likes of the US Army Marksmanship Unit and other resources.

- Try and find yourself a mentor or coach who you can run problems by; however please note that willingness to give an opinion is not always correlated with knowledge and skill!

- Finally, consider setting up a training group with a small number of like-minded individuals: share the cost of a SCATT, reloading equipment etc... I've seen this done in the UK which some success.

- For UK shooters, if you're of the right standard or even close to it, apply for the next GB U25 or GB touring team. Increasingly, team training sessions are focussed on just that - training - and not on selection or doing lots of shooting.

* Coaching in the sense of mentoring athletes to improve their performance, rather than the shooting sense of someone who reads the wind in a team match.